Scientists trying to understand the hunting behaviors of bottlenose dolphins have come up with a unique solution: fit them with video cameras.

The result is the most remarkable insight into the hunting process of dolphins seen so far, showing crucial details of their search for prey — and recording their squeals of victory when they catch some.

One dolphin is even seen hunting and eating several venomous sea snakes, a surprising and dangerous choice for a meal that scientists can’t fully explain.

The videos, released Wednesday, are an “incredible addition” to the scientific knowledge of dolphins hunting in the open ocean, biologist Brittany Jones of the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit group based in San Diego, said in an email. The scientists observed “eye movements, capture strategies, and movements of the lips, tongue, muscles, and gular [lower jaw] region during prey capture events which would be very difficult to achieve with wild dolphins.”

Jones worked closely with the authors of a research paper based on the video published in the journal PLOS One. The lead author is Dr. Sam Ridgway, a former foundation president and a renowned marine mammal veterinarian and scientist who died in July.

Under Ridgway, the foundation partnered with the U.S. Navy on its Marine Mammal Program, which trains bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions as underwater “watch dogs” to detect explosives and other objects in harbors and at sea. About 70 dolphins and 30 sea lions are in the program, which is also based in San Diego, and the partnership has yielded more than 1,200 scientific studies of their physiology and behavior.

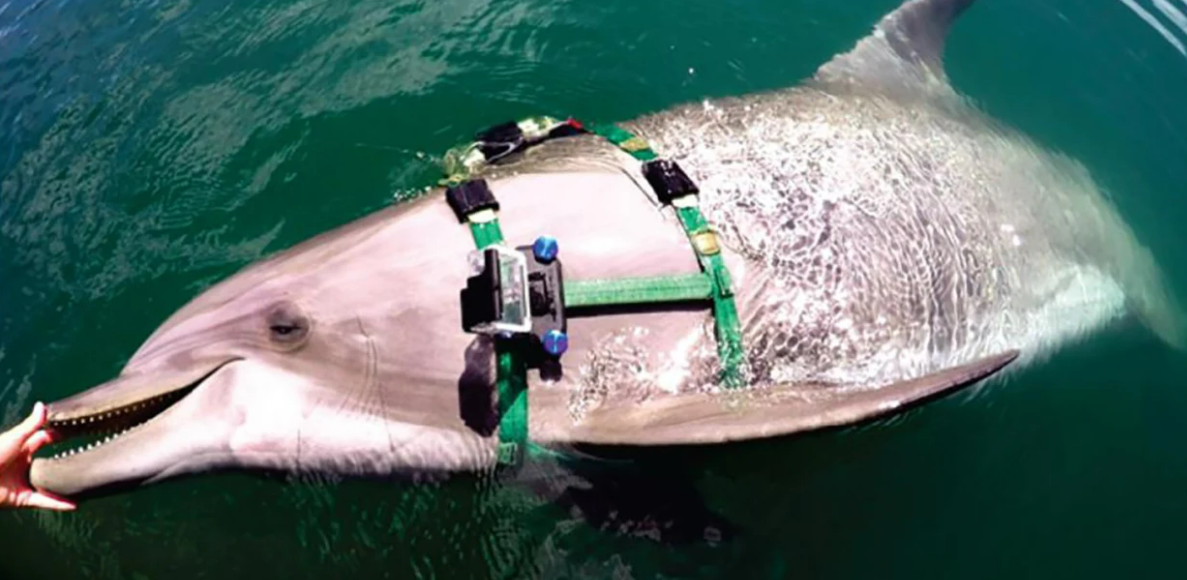

For the latest study the researchers fitted six U.S. Navy dolphins — identified in the study only as B, K, S, Y, T and Z — with a harness and underwater video camera that could record their eyes and mouths. The cameras also made audio recordings of any noises.

Study co-author Dianna Samuelson Dibble, a foundation biologist, said the video and audio give scientists unique insight into the hunting behavior of bottlenose dolphins. Although the dolphins in the study aren’t wild, they have frequent opportunities to hunt in the open ocean and the scientists expect wild dolphins hunt in much the same way.

Of special note are the sounds they make while hunting. The dolphins made “clicks” every 20 to 50 milliseconds as they looked for prey, a rapid noise that only they can hear clearly and which seems to be a form of echolocation — the natural sonar sense used by dolphins, porpoises and toothed whales to detect fish by bouncing sounds off them.