Henry Winkler, an actor, producer, and author of children’s books, has faced more challenges than most throughout his career. The skilled actor is most known for his role as Arthur “Fonzie” Fonzarelli, the greaser on the hit comedy “Happy Days,” which he shared with Ron Howard from 1974 to 1984. His character would eventually become more well-liked than other characters on the program, which prompted the writers to give him an even larger role. He was so effective as the bad boy with a good heart that he received two Golden Globe nods and three Primetime Emmy nominations for the part.

Winkler became well-known because to “Happy Days,” but he didn’t want to stay forever portraying bad boys. This is the reason Winkler declined the lead role in the movie “Grease,” which was ultimately given to John Travolta and went on to become a huge hit. He replied, “Because I’m an idiot,” when asked why he had shot it down.

He had some difficulty getting roles in the 1980s and the first few years of the 1990s, which prompted him to try his hand behind the scenes. He achieved success as a producer and director, working on projects like the wildly popular “Macgyver” series.

He became a master comedic actor in his latter years, portraying memorable characters on hit television programs including “Arrested Development,” “Parks and Recreation,” and even “Barry,” an HBO dark comedy series for which he earned an Emmy. He first appeared in “The Waterboy” with Adam Sandler in 1998, and he then appeared in “Little Nicky,” “Click,” and “You Don’t Mess With The Zohan.”

Winkler has struggled with a serious learning problem his whole life, which makes his career all the more astounding.

Winkler has never hidden the fact that he had a really difficult upbringing. Winkler’s parents left Germany on October 30, 1945, in order to avoid the Holocaust, and they eventually landed in New York. To The Guardian, Winkler described his relationship with them as follows:

“On the one hand, I’d admire my parents for leaving Nazi Germany in 1939, embarking on a new life, and providing us with a fantastic upbringing. On the other side, I’d say they were damaging emotionally. My parents didn’t pay attention to anything, despite the fact that a heard child is a powerful child. I never felt understood.

Additionally, he stated, “My parents never saw the person. Although I now respect them and their journey and am glad for the life I have been given, I did not like them when they first came into my life.

Winkler had trouble in school and was ridiculed by his relatives, who called him a “dumm hund,” which is German for “dumb hound.” Winkler’s early years were marked by anxiety and stress due to this disagreement. His relationship with his parents became strained as a result of the frequent punishment he received for his subpar grades.

“For the majority of my time in high school, I was grounded. They believed that if I remained at my desk for a period of six weeks, I would succeed and they would stop the absurdity of my sloth, he claimed.

Winkler didn’t understand he was dyslexic until he was 31 years old. He discovered this problem when assisting his stepson in school, who also struggled with learning. But it was too late to mend his relationship with his parents by this point.

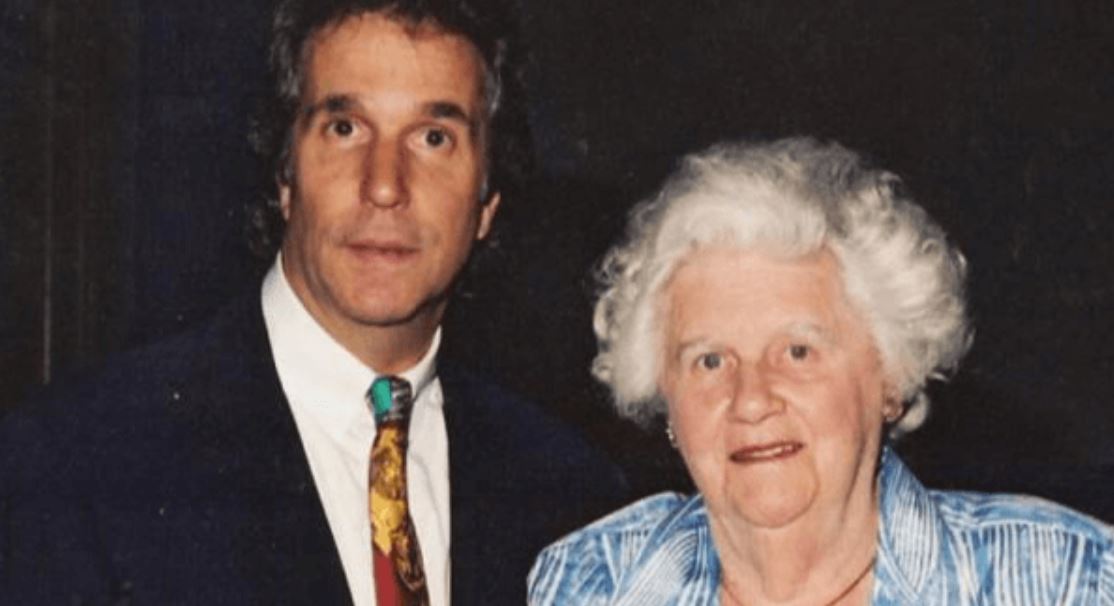

In 1989, Ilse Anna Marie Winkler, Winkler’s mother, experienced a crippling stroke. She developed upper limb spasticity as a result. Winkler stated the following about the condition:

The primary muscles, which are weakened and destroyed, are replaced by the secondary muscles in the arms, which then lock the arm into place. Additionally, the arm is frequently frozen out to the side, up against the chest.

Despite counseling, he continued, his mother did poorly: “She wouldn’t even leave the home in her wheelchair because it was so embarrassing. She didn’t even want to push herself.

Winkler put aside his emotions to take care of his mother despite the pain of his adolescence. This was challenging, though, as he was living in California and his mother and sister were in New York. It was difficult to share the load with her, and I felt bad when I couldn’t. I was quite grateful to my sister for filling in for me when I was unable to.

Winkler did his best to provide for his mother while he was away. “Support on the phone, daily talks, and then when I wasn’t working, travelling to New York as much as I could,” was how he achieved this.

In 1998, Winkler’s mother passed away. Despite his less than ideal relationship with her, Winkler learned from the experience to be motivated to raise his own children differently.

Winkler and his wife Stacey Weitzman, whom he wed in 1978, have two biological children together as well as a stepson from her previous union. His difficult upbringing at the very least prepared him to be a good father. “No matter how insignificant the interaction, every interaction you have with a child is recorded by that child. Adults are extremely strong. Children look to adults for, uh, self-validation.